Can the Tate clean up its defaced Rothko?

Attack on the artist's Maroon On Black throws up questions of security and whether the painting can be restored

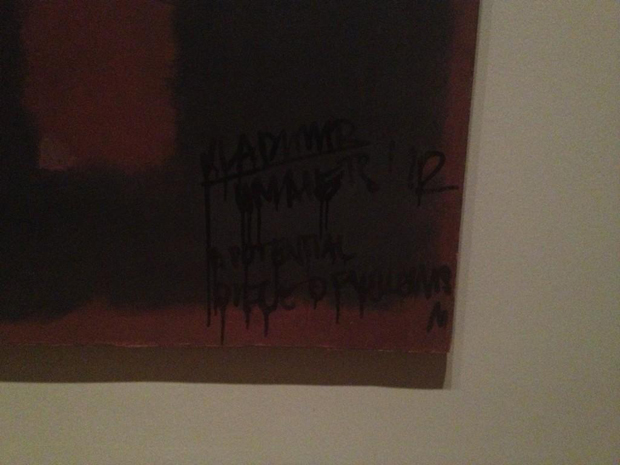

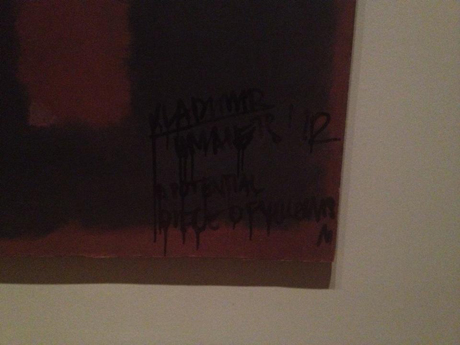

The question on everyone's lips this morning is just what can the Tate's restorers do about the scrawl on Mark Rothko's 1958 Black On Maroon canvas, which was vandalised on Sunday afternoon? As you may have read, a visitor to The Tate Modern defaced the work - one of Rothko's Seagram murals - before leaving the gallery without hindrance. This graffiti tag-style writing, which reads "Vladimir Umanets, A Potential Piece of Yellowism" has been attributed to Mr Umanets, a London-based artist. A man claiming to be Umanets spoke to The Guardian newspaper, explaining that he believes his defacement will increase the value of Rothko's work in years to come. However, The Tate, which was presented with the work by Rothko in 1969, understandably takes a different view. The creators of Yellowism say it is a "phenomenon" not an artistic movement. A Yellowism manifesto was written by Vladimir Umanets and Marcin Lodyga in 2010.It claims "Yellowism is not art or anti-art."

Instead, it is described as "an autonomous phenomenon in contemporary culture" which is "derived from the visual arts and despite this fact, is not classified as art, what is in accordance with its essence". In May, Umanets and Lodyga hosted an exhibition in London called No One Lives Forever. According to its website, the exhibition "brings together, in the surprising way, works presented before in the well known galleries, transforms them into the pieces of yellowism".

Fortunately, undoing Umanets's handiwork shouldn't be too difficult. As the British art conservator Julia Nagle explained to BBC Today Show listeners this morning, Rothko's paintings are relatively easy to restore. "The first thing you need to know is what the painting was originally made of," Nagle explained, "in order to distinguish between the solubility of what you want to get rid of and the original painting. Fortunately, in the case of Rothko, there's a massive body of research into his techniques - and a great conservation department at Tate." She added the graffiti would be "much more soluble because it is newer", meaning damage to the existing layers would be unlikely.

Indeed, this isn't the first time Rothko's works have been restored. In 2000, paintings at the Rothko Chapel, a gallery dedicated to the artist in Houston, Texas, were repaired, after a white film appeared on the canvasses. That was attributed to the environment in which they had been housed. Meanwhile, a series of Rothkos hung in a Harvard University dining room, were scanned for blemishes and discolourations back in 2010, before being re-hung under new, high-tech projection-style lighting, which lit the paintings in a such a way as to restore their missing pigments.