The truth behind Francis Bacon's 'screaming' popes

Father figure, drag queen or distillation of Nazi iconography? New Phaidon Focus book reveals the theories behind Francis Bacon's obsessive reworking of the papal theme in his most famous Velasquez-inspired paintings

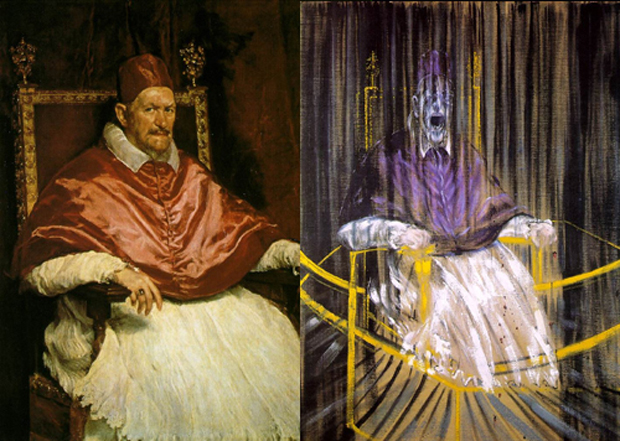

Around this time last week we brought you a look inside Anselm Kiefer's studio as part of a sneak preview from a Phaidon Focus book we're publishing on the acclaimed German artist. Today our Phaidon Focus is on a series of Francis Bacon's most famous paintings inspired by Velasquez's Pope Innocent X portrait. Scholars have pored over the paintings and the possible inspirations behind them ever since Bacon painted them in the 1950s.

Bacon worked on his pope paintings, variations on Velázquez’s magnificent portrait of Pope Innocent X, for over twenty years. He was already exploring the idea while in the South of France in late 1946. The first surviving version (Head VI) dates from late 1949, and he finally stopped in the mid-1960s. Subsequently, Bacon announced that he thought the works ‘silly’ and wished he had never done them. He acquired endless reproductions of the Velázquez painting from books, but famously did not see the original when he visited Rome in late 1954.

Clearly Bacon was not just producing homages to a picture he loved. Artists have always made copies as creative exercises, and Bacon may have been particularly inspired by the example of Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890), who made many transformations of pictures that he especially admired by Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863), Jean- François Millet (1814–1875) and others. Bacon’s popes depart even further from their source, often replacing the pontiff’s head with the equally recognisable screaming face of the wounded nurse mown down by the soldiers’ gunfire in the Odessa steps sequence of Eisenstein’s film Battleship Potemkin.

{media1}

The insertion subverts the encapsulation of power and self-assurance projected by Velázquez. The screaming mouth, isolated from other facial features and divorced from any narrative context, suggests existential agony. The pathos of human vulnerability and loss of faith or conviction are accentuated by the precisely rendered space frames in many Bacon images of popes, which make the figures register as ‘enclosed in the wretched glass capsule of the human individual’, to cite the evocative phrase used by the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche in The Birth of Tragedy (1872), one of Bacon’s favourite books.

The papal theme may have had a more contemporary resonance for Bacon, given that he embarked on his variations in 1946 immediately after the completion of Painting, with its dense references to Nazi iconography. He may have been attracted to the Velázquez picture as an iconic distillation of power, which made it such a vivid precursor to Fascist propaganda photography. In later works in the series, Bacon inserted references to photographs of the then pontiff, Pope Pius XII, a controversial figure who was thought by some to have appeased the Nazis. A photograph of Pius on his throne, being carried from St Peter’s, appears in one of Sam Hunter’s 1950 studio montages, and was clearly the basis for some of the subsequent pope pictures.

{media2}

Bacon’s obsessive reworking of the papal theme suggests that it may have possessed further significance and perhaps psychological charge for the artist in relation to his sexuality. It has been remarked that the Pope in official garb is in a sense the ultimate drag queen, or less literally that depictions of the Holy Father, known in Italy as ‘il Papa’, may encapsulate Bacon’s traumatic feelings about his own father. The latter was a conventional, inflexible military man to whom the teenage Bacon had felt sexually attracted, as he recalled many years later, but who brutally admonished and rejected him when he discovered his son’s homosexual inclinations. Such speculations about the possible ‘subconscious’ content of the pope pictures involve perhaps a rather crude application of the methods of Freudian psychoanalysis. Once again it is neither altogether possible nor helpful to pin Bacon down.

The Phaidon Focus series is designed as a lively, authorititive and accessible introduction to the work of the artists featured in the (initial) six-strong series (Kim, the editor, is already hard at work on the next instalment). As the title suggests, each features special Focus sections that explore specific and important themes, series, pieces or events in each artist's career, so whether you're new to the artist or you already know a bit you'll come away enlightened and, we hope, nourished. Take a look at the series in the store.