How Joseph Beuys went from artist to philosopher

A new exhibition looks at Beuys's transition from a creator of artistic objects to a 'social sculptor'

These days, when we hear an artist want to change the world, we're often a little skeptical. Yet for the German sculptor, painter, draughtsman, teacher, theorist and political activist, Joseph Beuys (1921 - 1986), his artistic ambition was almost indivisible from a more concrete ambition to remake society for the better.

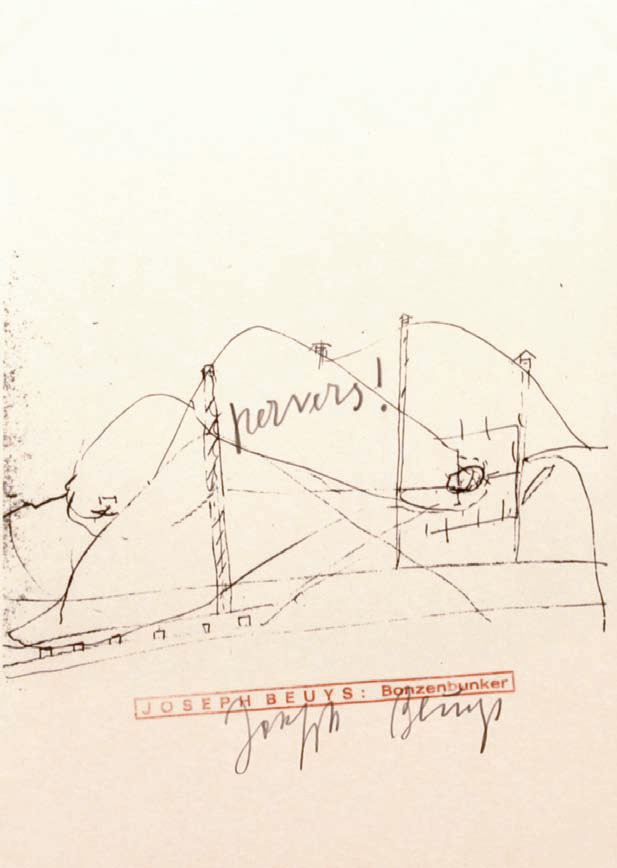

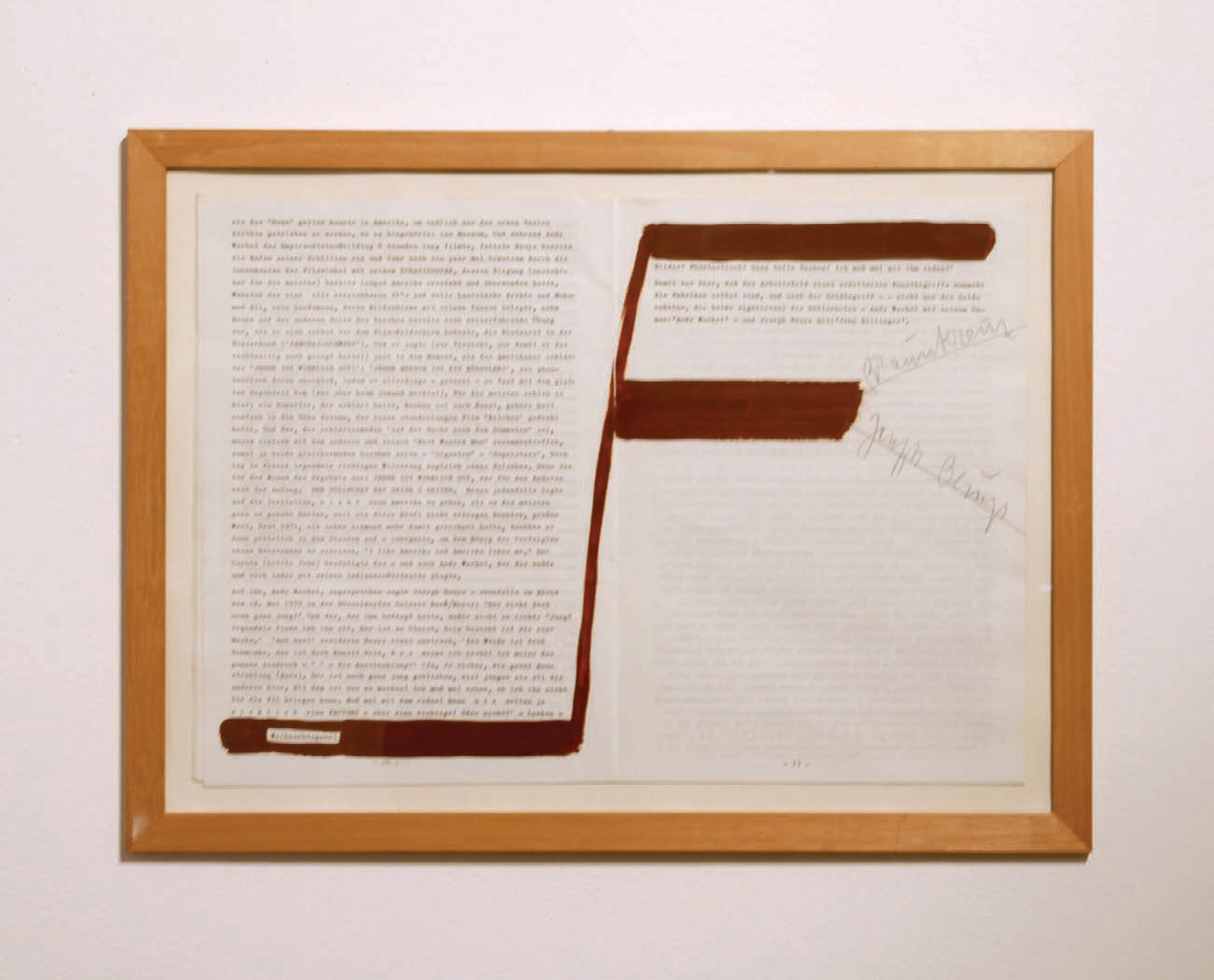

A new exhibition, Process, running at the Rooster gallery at 190 Orchard St in Manhattan focuses on Beuys's work 1971 - 1985 when, in the words of Kara L Rooney, the show's curator, he went from "maker of objects to artistic philosopher." Our new Phaidon Focus book on the artist, written by Allan Antliff, helps us understand this shift a little better.

"Along with protests against the threat of nuclear annihilation and the war in Vietnam, many were seeking alternatives to the communist and capitalist social-economic systems dominating Western and Eastern Europe," writes the art critic.

"This set the stage for Beuys's entry into the realm of leftist politics under a new, challenging, artistic banner: social sculpture."

This term was used to describe Beuys's attempts to remake German society, a little like a sculptor might chisel rock. "Beuys pushed the boundaries of what constitutes art, declaring 'everyone is an artist'," Antliff continues, "and coining the term 'social sculpture' to encapsulate his anarchic programme for transforming society."

It was neither left nor right wing ideology that drove Beuys, but rather the writings of Austrian philosopher Rudolf Steiner. Here's a bit from the book again:

"Steiner believed that freedom is the foundation of spiritual growth, not only for society but also for the individual. Creativity is defined as an activity undertaken by individuals who are fully conscious of their intentions. Humanity's capacity to gain knowledge is an exercise in spiritual growth through creative thought, which extends our sense of selfhood beyond the realm of the physical into the realm of the spiritual."

These beliefs were alloyed in Beuys's thinking with post-war, anti-nuclear and ecological concerns. Yet his works were never charmless or overly didactic. Take this artful demonstration, from 1971.

"That December, Beuys and fifty students demonstrated how direct action could work by sweeping paths through a small public forest in the city of Dusseldorf that was threatened by the planned expansion of a tennis club," writes Antliff. "They marked the trees that were to be cut down, exposing just how devastating the destruction would be. Beuys issued a call to 'Overcome the dictatorship of the parties, save the forest!' and distributed a poster announcing 'Let the rich beware, we will not yield. Universal well-being is advancing.'"

Perhaps the artist's most ambitious work from this period was Take Honey Pump (1977), made for the dOCUMENTA VI arts festival of that year. Antliff writes, "Honey Pump at the Workplace (Honigpumpe am Arbeitsplatz), was a remarkable installation comprising 220 lb. of fat being continuously stirred in a copper cylinder, two tons of honey circulating through the Free University discussion space from a steel container, a pump mechanism and Plexiglas tubing. The honey was pumped from the steel container located in a stairwell up a bent pipe and into tubing that snaked through the area where the Free International University was taking place and back down the stairwell to the container.

"The Honey Pump installation suggested that social sculpture was a vital force for renewing 'the bloodstream of society', as Beuys put it. It also metaphorically presented Rudolf Steiner's model of the three psycho-physiological 'sites' in the human body: the head, seat of the nerve system, which facilitates thought; the chest, which is the seat of sensation and the rhythmic functions crucial to life; and the metabolic system of limbs, which realize the commands of the will. The site of the Honey Pump's 'chest' was the stairwell containing the steel container, pump mechanism and fat-stirring engines; its 'head' was the pipe connected to the container that extended up from the stairwell and bent in a crook at the top to connect with the tubing in the exhibition hall itself; and its 'metabolic system' was represented by the copper cylinder mechanism for stirring the fat. The creative work being realized by Free International University participants was represented by three empty bronze pots near the honey container, which stood in for the threefold spiritual aspect of human beings: 'imagination, inspiration, and intuition', in Steiner's parlance."

Unfortunately, Rooster hasn't the original of this work, but they are showing plenty of Beuys works that sum up this time. Look out for Capri Battery (1985), an environmentally themed work, consisting of a lemon and a lemon-coloured lightbulb, which, as Antliff puts it, suggests that, "the integration of the man-made world and nature might be easier than we think."

There's also Element, his 1982 edition of two angular copper and iron plates which dwells on the old symbols for the metals: the unbending iron was represented with a male symbol, while the softer copper has long been given a female symbol, giving rise to questions of gender roles and values.

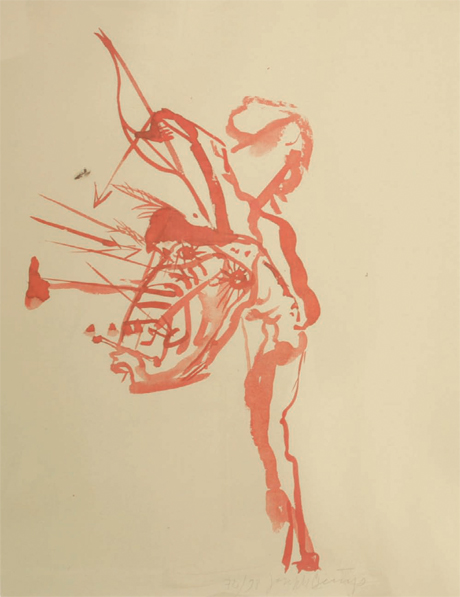

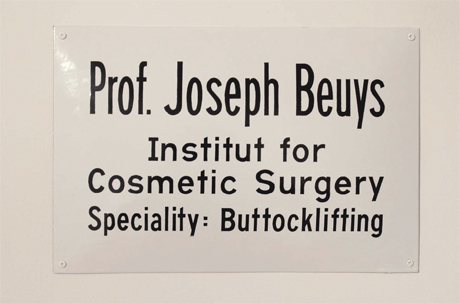

There's also the numinous photo etching, L'arte è una Zanzara Dale Mille Ali (Art is a Mosquito with a Thousand Wings), (1981), written in Italian as Beuys occasionally did, and the more blunt, punky enamel sign Buttocklifting (1974).

These near-baffling works might not look like the kind of thing likely to change the world for good. Still, a little under three decades since Beuys's death, Germany, having under survived both Nazism and a fairly toxic style of Communism, is now one of the most, tolerant, civilized ecologically sound and economically successful countries in the world. Did Beuys's work help nudge the country towards this state? Surely it played a part.

For more on the show, which runs until 9 February, go here. And for greater understanding of this complicated artist's life and work, order our new title, as a hardback here, and as an ibook, here.