How Raphael won his place within the Renaissance

On the anniversary of his birth, and death, read how his easygoing nature helped him secure a place in art history

There are many lessons to be learnt from the Italian Renaissance, for artists, scientists and philosophers. Yet one artist’s life and success might even offer instruction for today’s management consultants. And it seems like a timely lesson as he was born on - and died on this day, April 6 (1483-1520).

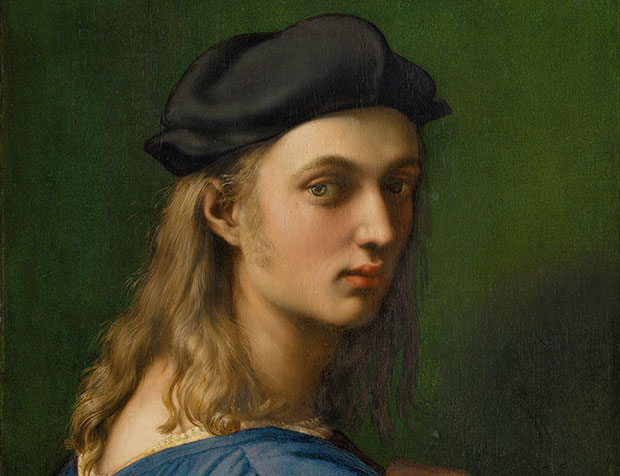

When the young Italian painter Raphaello Sanzio arrived in Florence in 1504, he had to overcome the challenge of working in a city where some of the greatest artists ever known were creating their masterworks. Leonardo da Vinci, 31 years his senior; and Michelangelo, eight years older than Santi, were both producing the kinds of art no one had dared imagine a generation earlier.

How did the painter who we now know as Raphael find his own place alongside these renaissance Titans? By working hard and being nice to people, it seems.

“He had neither the immense range of knowledge of Leonardo, nor the power of Michelangelo,” the great art historian EH Gombrich explains. “But while these two geniuses were difficult to get along with, unpredictable and elusive to ordinary mortals, Raphael was of a sweetness of temper which would commend him to influential patrons. Moreover he could work, and work he would until he had caught up with the older masters.”

This is not to say that Raphael's talents were limited to his interpersonal skills. He remains one of the great Renaissance artists. Yet his even-tempered manners and disposition found expression in the undeniable harmony and balance of his paintings.

As Bette Talvacchia, distinguished professor of art history at Connecticut University writes in our updated Phaidon classic Raphael: "His art never fails to engage the viewer's imagination, whether through the mesmerizing, graceful beauty of his Madonnas, the perfection of his classicizing forms, or the inescapable pull of his narrative scenes." Or, as Gombrich puts it, “some of his best works give us a glimpse into a world more serene and harmonious than our own.”

Moreover his working practices gave rise to that perverse, yet unusually common quality found among those who really strive hard: he made his labours look effortless. As Gombrich puts it, “Raphael’s greatest paintings seem so effortless that one does not usually connect them with the idea of hard and relentless work.”

Raphael’s Madonna paintings became the standard representation of this Christian figure, to such an extent that his paintings now look somewhat commonplace. Yet, as Gombrich explains, “if we compare it with the countless representations of the same theme which preceded it, we feel that they have all been groping for the very simplicity that Raphael has attained.”

More strikingly, when grouping figures together, Raphael managed to achieve a level of harmony unseen before; when decorating the Vatican with his frescos, he gave rooms both a diversity and an accord of imagery.

Before his death, on his birthday at the tender age of 37, he had bested his contemporaries in at least on regard. “Just as Michelangelo was found to have reached the highest peak in the mastery of the human body, Raphael was seen to have accomplished what the older generation had striven so hard to achieve: the perfect and harmonious composition of freely moving figures.”

Indeed, our opulent new Classic edition of our Raphael monograph could run to even more pages, as Raphael’s likable disposition suited the Renaissance workshop system, wherein a master artist would oversee an atelier of junior artists.

“Unlike his great rival Michelangelo, he got on well with people and could keep a busy workshop going. Thanks to his sociable qualities the scholars and dignitaries of the papal court made him their companion. There was even talk of his being made a cardinal when he died on his thirty-seventh birthday.”

Perhaps we should give thanks for the art he managed to produce in his relatively brief working life. To understand this great artist order a copy of our new Phaidon Classic edition of our Raphael monograph. And for a fuller understanding of his place in the Western canon order a copy of EH Gombrich’s The Story of Art. And while you're in the store check out our newly release Phaidon classics, Vermeer, Renoir and Botticelli.