Stories from the Secession - how Vienna led the world

Our book Art in Vienna looks back at the radical developments that took place in the Austrian capital a century ago

We can all picture the great works of Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele, but how about the city they were created in? Art in Vienna 1898-1918, Peter Vergo’s study of Viennese art and architecture in the first two decades of the century is an indispensable guide to an extraordinary and colourful efflorescence of cultural activity, featuring a range of artists, including Klimt and Schiele.

Indeed, the city's creative achievements are all the more impressive when you consider that in 1900 the capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire was home to fewer than two million inhabitants.

Although Vienna was, as the author Robert Musil pointed out, “somewhat smaller than all the world’s largest cities”, at the turn of the 20th century it was the centre of a flourishing and technologically forward looking society; in 1899, it had hosted the first ever international automobile race. It was also home to great composers such as Mahler and Schoenberg, who was on the point of revolutionising 20th century classical music with his atonal compositions. Meanwhile, 1900 was the year in which fellow Viennese citizen Sigmund Freud published The Interpretation Of Dreams, in which he first introduced his theory of the Oedipus Complex.

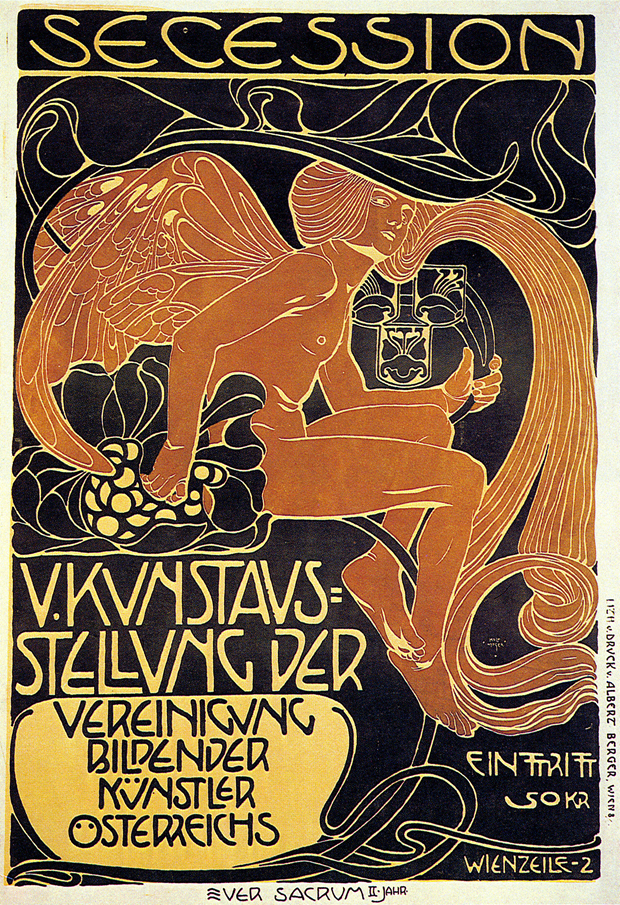

Despite its progressive liberalism, however, Vienna was also deeply conservative and stolidly bureaucratic, oblivious to the impending decline of its thousand-year empire. “The slumbering city vegetates in its own mediocrity and does not dream what great things are being thought and created in her midst”, wrote Otto Friedländer. It was even actively hostile to the radical developments it hosted, eager to block the galloping progress in the arts. The re-election of the ultra-conservative Eugen Felix to the presidency of the Künstlerhaus, the influential exhibiting society threatened the exposure of revolutionary artists like Klimt. And so it was that in 1897, he and 12 other artists resigned from the Künstlerhaus to form what would become known as the Viennese Secession.

The Secession was an active riposte to the historicism of the Künstlerhaus and of the academic tradition in general. Now was the time to dispense with artistic precedents and find new ways of presenting art. It was international in outlook, and through its exhibitions brought the French impressionists to Vienna, whose work would itself exercise a significant influence on the Secessionist artists. It also placed a great emphasis on applied art, showing how it could impinge on everyday life rather than sit in grand, fusty remoteness. There was no particular “Secessionist” style, merely an outlook summarised in the slogan inscribed above the Viennese Secession building, “To every age its art. To every art its freedom.” By 1900, the Secession had its own journal, Ver Sacrum (Sacred Spring) and was establishing an art movement that, unlike the Austrian empire, would last the ages. Springtime indeed for a new epoch.

We hope you’ve enjoyed this brief overview of the city. Look out for our next story from the Secession, and for a richer understanding of the time buy a copy of Art in Vienna 1898 – 1918 here.