What happened when Sarah Sze was censored

By changing one of her apolitical pieces the Chinese Government inspired Sze to create a more critical work

The artist Sarah Sze does not make simple, didactic, banner-waving works of art. Instead, as we explain in our Contemporary Artist Series book dedicated to her, the artist “creates intricate site-specific pieces that exist at the intersection of sculpture, painting and architecture.”

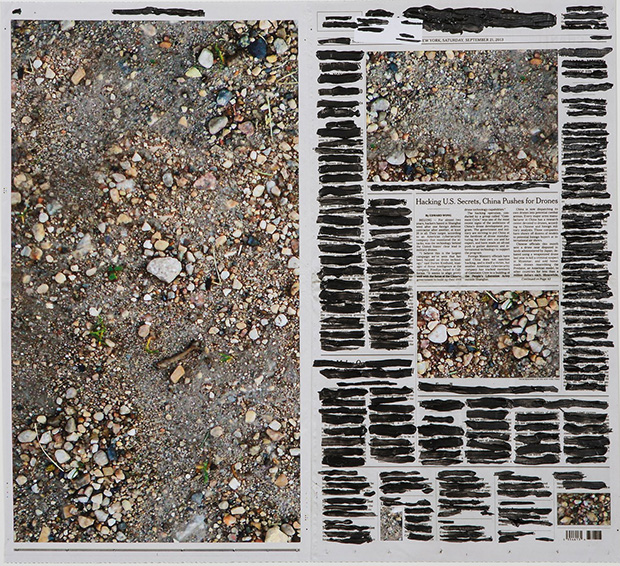

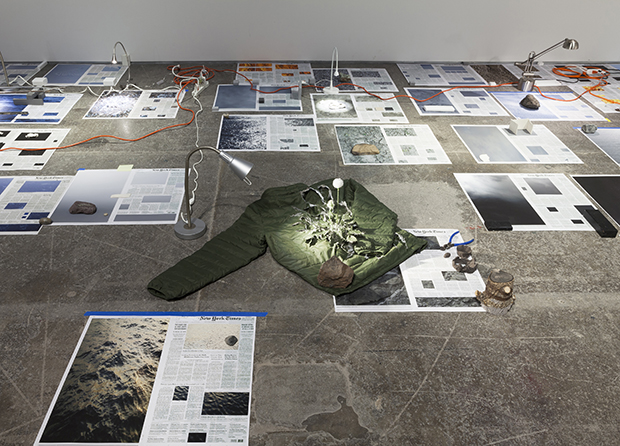

Why would a Chinese state censor find fault with her? Perhaps because they read a little too much into her work. For last year’s Guangzhou Triennial the artist submitted her Calendar Series. In these pieces Sze took the front page of the New York Times newspaper, cut out the photographs and replaced them with less immediate images.

“There could be an image of the ocean, an image from 500 years ago,” the artist told the Guardian. “I was interested in contrasting what was newsworthy with these timeless images.”

Unfortunately, this was seized upon by the Chinese government, who asked Sze to censor any story within the presented cuttings that mentioned China.

“It was amazing to me that the Chinese government actually paid such attention,” she says. “It suggests a belief that art has a major influence on society.”

Sze changed her works. "I made a new version for China," she explained. "The piece was actually on the floor, like it was protecting the floor, spattered with paint and so on. So I took black paint and painted out the parts they wanted redacted and then mentioned the fact in the wall note."

However, in response, Sze has also created a counterpart to these censored Calendar Series works for a new exhibition at London’s Victoria Miro gallery focusing on the subject of political activism. For the show, entitled Protest, Sze has recreated her Guangzhou Calendar Series works, obscuring all the texts apart from the passages the Chinese government asked her to censor. In this way the censors actually allowed Sze, whose art tends to deal with the multifarious ways we take in and respond to messages, to direct her attention towards a single political cause.

"For this show I have done the opposite," she says. "I left in all the pieces I had redacted and painted black all the rest of the text. Protest requires focus,” she goes on. “If the Occupy movement could have focused around one moment or image – like John and Yoko in a bed – it would have helped that movement a lot. My work really reflects the sense, I think, that we have masses of information coming at us from sources we don’t know, and the speed of that makes the hierarchy of what to protest against very slippery all the time.”

To get a better handle on that slipperiness, order a copy of our Sarah Sze book here, or browse through the Sarah Sze works for sale over on Artspace.