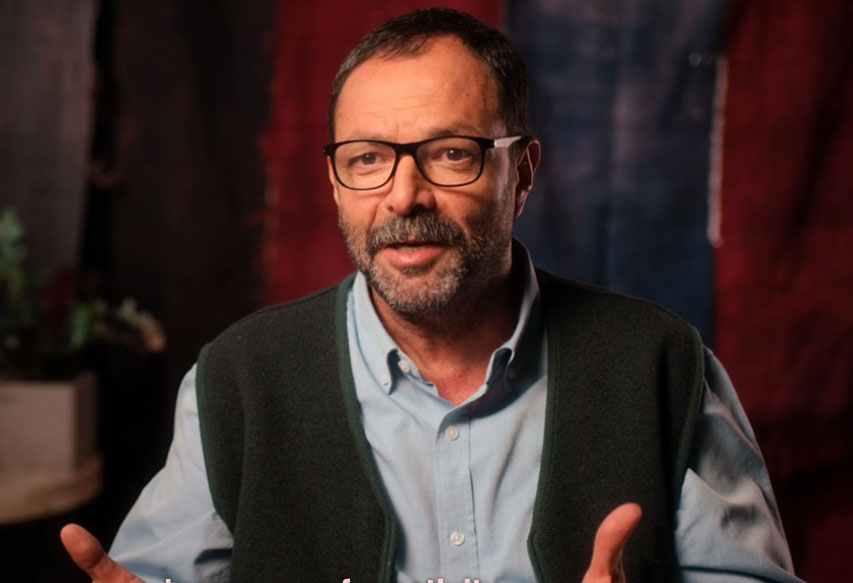

Meet Musa Dağdeviren, the saviour of Turkish cuisine

The Turkish Cookbook’s author isn't impressed by modernisation, he wants to preserve his country's great recipes

What sort of a chef saves his country’s culinary traditions? One like Musa Dağdeviren, who was more or less born to love food. “Relatives on my father’s side were farmers, and on my mother’s side bakers, ” the author of The Turkish Cookbook says. "In Nizip, Gaziantep, where I am from, food meant everything to us.”

Dağdeviren was born in this city in south-eastern Turkey in 1960 and began working in his uncle’s bakery at the age of five – a place that not only produced bread, but also drew in other culinary professionals.

“There used to be many street vendors who cooked chickpeas in bone broth and pulled their carts in front of bakeries for hungry aficionados in the early morning,” he recalls in the introduction to our new book. “The baker, butcher, greengrocer, kebab shop and pastry shop were all in the same area.”

When he wasn’t helping make bread, Dağdeviren used to talk food with his friends. “During primary school we used to compare our mothers’ food,” he explains. “Every mother had a special dish she made really well. I have always been interested in ingredients and cooking techniques. This curiosity eventually led me into my research and field work on the relationship between food and folklore.”

In this respect, Dağdeviren is an unusual chef. As fellow Turkish chef and TV star Mehmet Gürs explains in the Netflix documentary dedicated to Dağdeviren’s work, “He [Dağdeviren] doesn’t give a rat’s ass about contemporary food or taking the tradition and bringing it to the future.”

Dağdeviren, unlike many of those who run the kind of restaurants that occupy the top spots in the World’s 50 Best list, doesn’t want to reinvent or modernise his national cuisine; he simply wants to preserve traditions he has seen disappear.

“In the 1980s we cooked with diverse ingredients, most locally produced,” he remembers. “Street vendors and restaurants contributed to a vibrant and authentic food scene which is sadly no longer here because of wider access to mass-produced foods. The local food culture that was dominant in Nizip in my childhood has long been replaced by restaurant food. Restaurants do serve local specialties like ridged bread, pide, lahmacun, sheep’s head and trotters soup, lentil soup, karnıyarık and moussaka. More efficient communication and urbanisation have unfortunately taken place at the expense of local cuisines.”

At Dağdeviren’s restaurants in Istanbul, he’s managed to hold on to these older traditions, while elevating the place of simple, regional foods.

“I worked at several restaurants and did a fair bit of field work before opening a tiny restaurant with four friends in 1986,” he writes in our book. “This six-table diner eventually turned into Çiya and I eventually became the sole owner. This boutique hole-in-the-wall is still remembered with affection by aficionados. I would take orders for special dishes and cook them for the patrons who enjoyed them accompanied by classical music.”

“I experimented passionately with new foods, reading extensively and researching obscure local dishes in Anatolia,” he recalls. “In 1998 we opened Çiya Sofrası, on the same street but with a new concept.”

This new place gained a reputation for recreating little-known dishes from the wider region, including Southeastern Anatolia and the Eastern Mediterranean. “It encompasses a larger area from Mesopotamia to Anatolia featuring Azeri, Georgian, Turkish, Arabic, Armenian, Kurdish, Rum, Assyrian, Laz, Circassian and Sephardic dishes,” the chef explains.

At the turn of the 21st century, he opened a kebab restaurant, and now Dağdeviren has his own farm, which supplies his restaurants. “We make our own pickles, grow our own fruit and vegetables and make our own tomato and red bell pepper pastes with the ingredients we grow ourselves,” he writes.

Many chefs would be content with this mini Empire, keeping Turkish food alive, yet Dağdeviren is still hungry for fresh knowledge. In 2005 he founded his own publishing house, producing books that detail Turkey’s food, folklore and culinary history, and in preparation for The Turkish Cookbook, he struck out into his country’s hinterland to gather more recipes. “Fieldwork was the most fun part,” he writes. ”I visited people in their kitchens and made them food, while they cooked for me in return."

"To find out more about the dishes Dağdeviren cooked and collected, and the fascinating stories behind them, order a copy of The Turkish Cookbook. It has 550 recipes for the home cook that celebrate Turkey's remarkable European and Asian culinary heritage – from little-known regional dishes to those that are globally recognized and stand the test of time, be they lamb kofte, chicken kebabs, tahini halva, or pistachio baklava. Find out more here.