The elite students who remade the world under Walter Gropius

The later chapters of our new illustrated biography look at how the Bauhaus master influenced Richard Rogers, IM Pei, and Norman Foster, among many others

In their new book, Walter Gropius: An Illustrated Life, authors Leyla Daybelge and Magnus Englund single out not one, single biographical tale, but three distinct ‘lives’ lived by this titan of 20th century architecture. The first took place in Germany, where the young architect became one of the founders of the modern movement, creating his first major buildings in the second decade of the twentieth century and founding the Bauhaus in 1919.

“Gropius’ second life was as a celebrated but impoverished exile from Nazi Germany,” explains the book, “living in London between 1934 and 1937. Although his architectural output during this period was limited to just a handful of commissions – two houses, a school and a film laboratory – his lectures, unrealised projects and presence at the centre of a dynamic artistic community helped to galvanise the forces of Modernism in Britain and left a lasting legacy in the teaching of architecture and design.”

Yet it is in the final section of this visual biography that Gropius is perhaps viewed at his most influential. “His third and last life took him to the United States where, as head of the Graduate School of Design at Harvard University, he played a major role in the development of the ‘International Style’,” the authors write. “His students – among them famous names such as IM Pei, Philip Johnson, Harry Seidler, Eliot Noyes and Paul Rudolph – became a global ‘dynasty’ who in turn inspired a third generation, including Richard Rogers and Norman Foster.”

While this tripartite take is neatly segmented via Gropius’s migration first to Britain then to America, the beginnings of this final US chapter were actually established while the architect was still in his native Germany. In 1930, the American architect Philip Johnson became the first director of MoMA’s Department of Architecture, explain the authors, “and in 1932 he initiated its first architecture show, the Modern Architecture: International Exhibition, which featured Gropius’ Bauhaus building. Its catalogue established ‘International Style’ as the US term for modern architecture,” they write, adding it was “a term Gropius much disliked.”

Regardless, the term stuck, and still serves as a useful way to describe the kind of late modernism that Gropius helped to disseminate around the globe. Our new book places strong emphasis on Harvard's generosity, when, in October 1936 the university offered Gropius “the prestige of a high-status academic role with the added freedom to pursue a private architectural practice.”

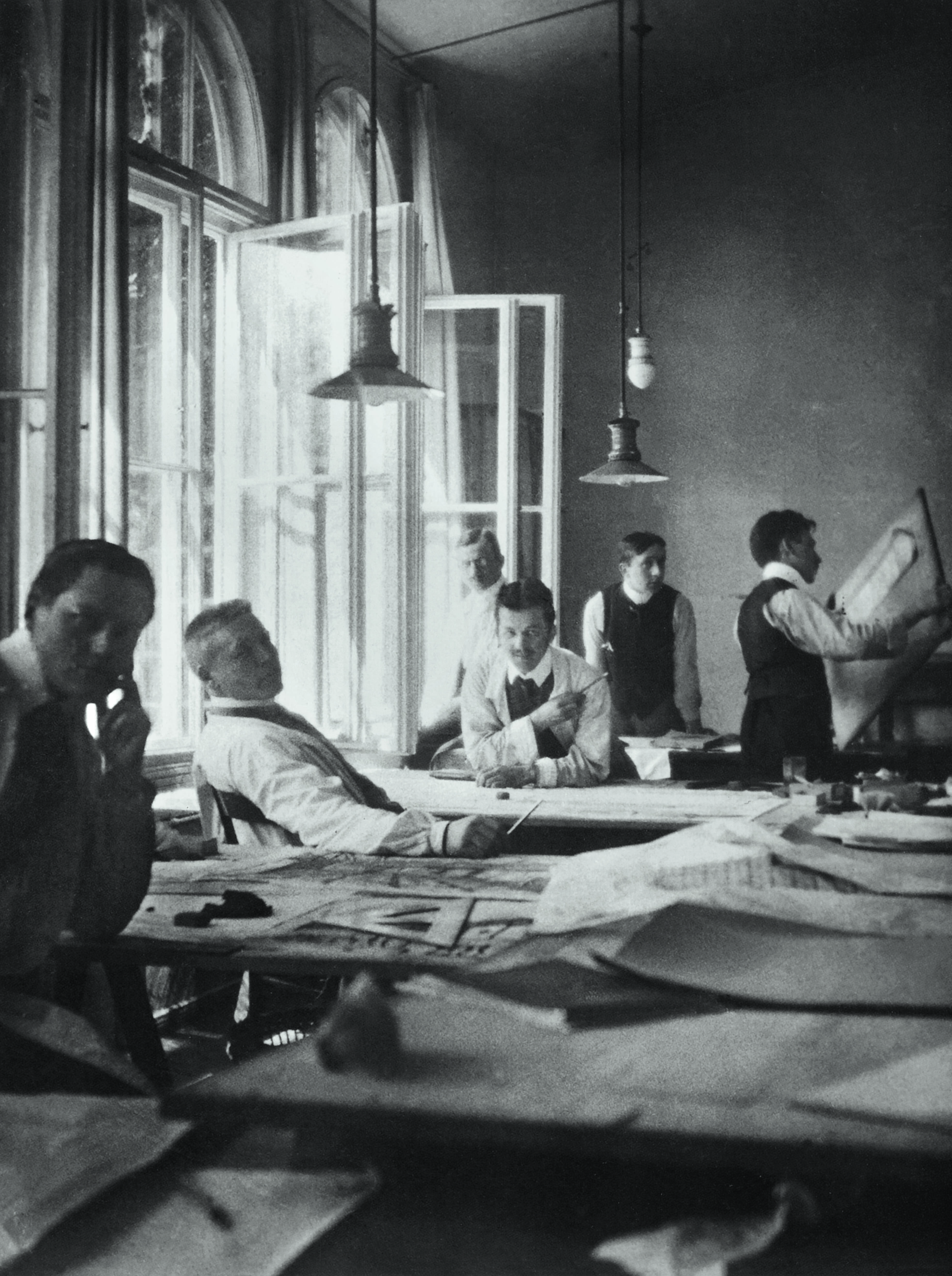

Walter Gropius (far right), Peter Behrens' Babelsberg office, near Potsdam, 1908

Not only a great architectural practitioner but also a great teacher, this late stage US career enabled Gropius to disseminate his style of building across the globe.

In the early 1950s, his contemporary, Le Corbusier would observe, “Gropius has radiated his qualities upon students from all quarters of the earth. It has been the good fortune of America to provide both the place and the budget, but the name of Gropius is pronounced with reverence over the entire world.”

Those who passed through his classrooms at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design “included Philip Johnson, IM Pei, Harry Seidler and Paul Rudolph, who, as Chair of Yale School of Architecture, in turn taught Norman Foster and Richard Rogers,” notes the book.

However, the architect also laid the foundations for the subsequent modernist backlash, through some of his more notable works from this time.

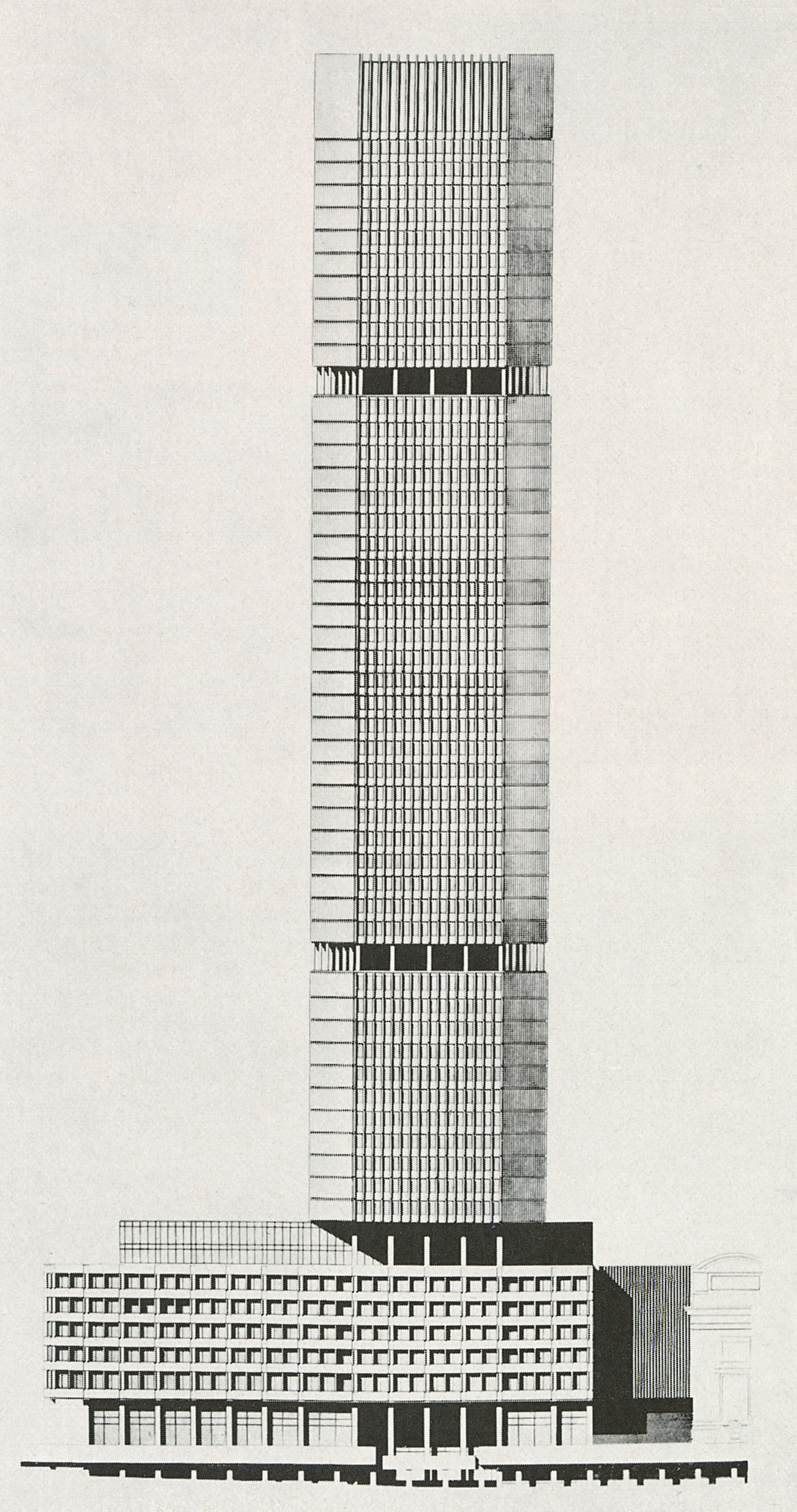

The book focuses on Gropius’s work on the Pan American headquarters in New York at 200 Park Avenue.

Gropius was brought in late on the project by its developers to act as an ‘artist–architect’, diffusing criticism levelled at the initial architectural plans drawn up by Emery Roth & Sons, “a major firm known for efficient but bland office blocks, many of which littered Park Avenue,” explains our new book.

Yet his work here actually stirred up public complaint. The new book explains how the German architect “changed Roth’s idea of the building along the axis of Park Avenue and swung it ninety degrees, straddling Park Avenue from side to side. The tower dwarfed Grand Central station in front, and blocked the sight lines along Park Avenue. By the time the building was completed in 1963, it was vilified, accused of ruining the appearance of one of New York’s most beautiful buildings, adding massive congestion to an already busy part of Manhattan and throwing the surrounding streets into darkness.

Gropius’s old friend and former student Philip Johnson publicly condemned the work, and even fellow architect Pietro Belluschi – who had been brought in to work on the project at the behest of the German – accused Gropius of not listening to the public, aligning himself with property developers and betraying his own social principles.

“The Pan American Building was a watershed moment: thereafter, Modernism was questioned and criticised in ever wider circles, eventually opening the way for postmodernism,” says our new book.

Is this fair? “Looking back, the MetLife (as it is now known) is no taller than other Manhattan towers and Gropius’s fine detailing of its facade, using quartz to make it glitter in the sun, as well as its distinctive shape make it a landmark,” the authors reason. “But at that time, and in that location, it became a lightning rod for much anger.” Yet it’s interesting to note that this great modernist pioneer may have carried out the groundwork for the subsequent architectural movement: postmodernism.

Walter Gropius: An Illustrated Life

To discover much more about this period of the architect’s life as well as many others, order a copy of Walter Gropius: An Illustrated Life here.