When John Cage met Robert Rauschenberg

How the artist’s seemingly simple paintings inspired one of the most challenging compositions of the 20th century

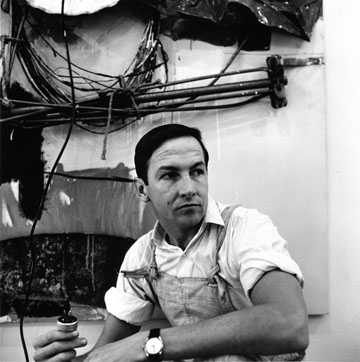

Artistic influence tends to travel down the generations, from senior practitioner to novice. Yet, on occasions, it can run the other way, such as when the American painter and sculptor Robert Rauschenberg met the avant-garde composer John Cage.

As author Catherine Craft explains in our Phaidon Focus title dedicated to Rauschenberg, Cage first met the painter and sculptor in May 1951, during the artist's debut solo exhibition, at the Betty Parsons Gallery in New York. Cage was in his late thirties, and well established within the field of avant-garde music; Rauschenberg, thirteen years his junior, was just starting out.

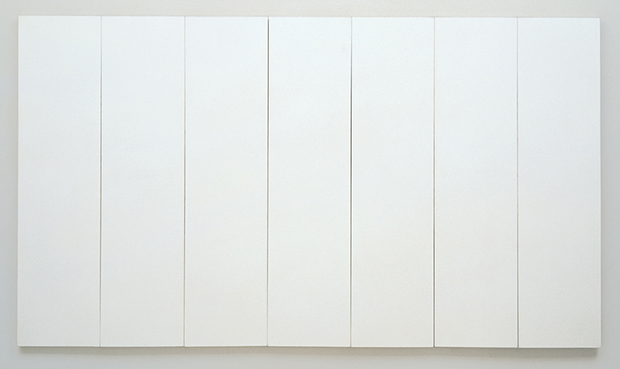

Nevertheless, it was the spirited innovation of the painter that most closely influenced the composer. In particular, Cage was taken with Rauschenberg’s White Paintings. In our survey of post-war art, Painting Beyond Pollock, author Morgan Falconer describes this seminal series of five, paneled works, which date from 1951, as being “painted on canvas in a smooth, unmodulated white, and structured in a sequence that includes one, two, three, four and seven panels.”

In Falconer’s mind, the abstract works should be seen less as works in the high, spiritrual register of Abstract Expressionism, and more as simple communication tools – an idea developed by Josef Albers, Rauschenberg’s tutor at the innovative, interdisciplinary arts institution, the Black Mountain College, where Rauschenberg studied 1948 – 49.

Whatever the influence, it was on returning to Black Mountain College in the spring and summer of 1952, that Cage and Rauschenberg’s creative relationship, which developed around these White Paintings, truly flourished. The remote college already had a reputation for artistic freedom and the breaking down of boundaries, having had Albert Einstein serve on its board of directors, and Buckminster Fuller teach classes.

In Black Mountain’s liberal campus during the balmier months of 1952, Cage looked to Rauschenberg’s canvases to inform his ideas about how art should engage with the intrusions of the natural world. As Craft explains, “Cage was astonished by the White Paintings, which showed him how artists could work with, rather than against, the ever-changing nature of their surroundings.”

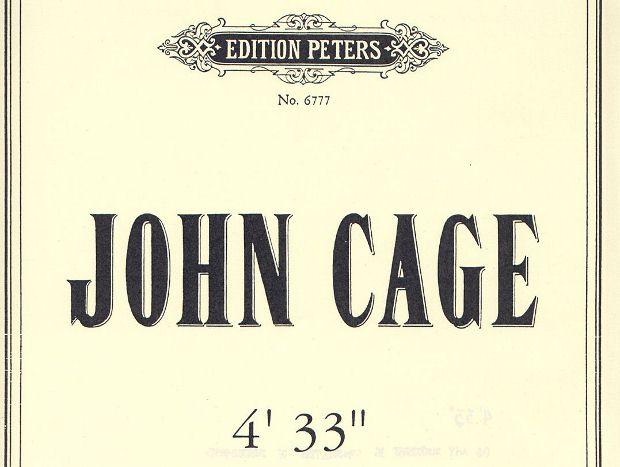

Falconer picks up the point in his book, where he writes: “Cage used the White Paintings as a backdrop for one of his concerts Theater Piece #1 (1952), and he later said that they were an important inspiration for his most famous composition, 4’33” (1952), an entirely silent piece in which the sound comes not from the pianist, but principally from the ambient noise of the concert auditorium.”

This idea of an artwork as a kind of backdrop for the world, was something Cage first recognized in Rauschenberg’s paintings.

“Cage viewed the White Paintings less as images that projected the artist’s expression, than backdrops against which the flux of the world might stand out, an understanding that he arrived at through his appreciation of Henri Bergson and Zen Buddhism. ‘The White Paintings were airports for the lights, shadows, and [dust] particles,’ Cage said. Rauschenberg would never immerse himself in these ideas with the same enthusiasm as his mentor, but Cage was important in shaping his outlook in these early years.”

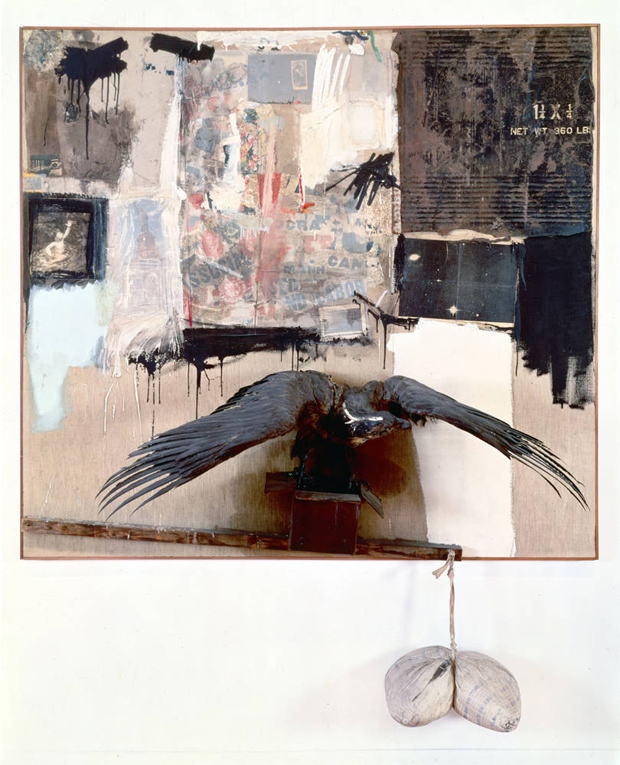

Indeed, Falconer suggests that one of Rauschenberg’s best-known forms, his ‘combines’ – or hybrids of painting, sculpture and college, were first developed for Cage, in response to a prop request to accompanying the performance of the composer’s 1954 work, Minutiae.

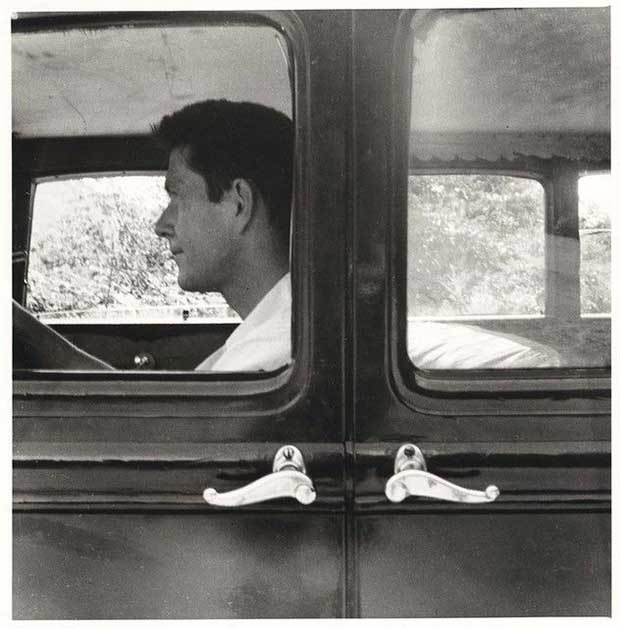

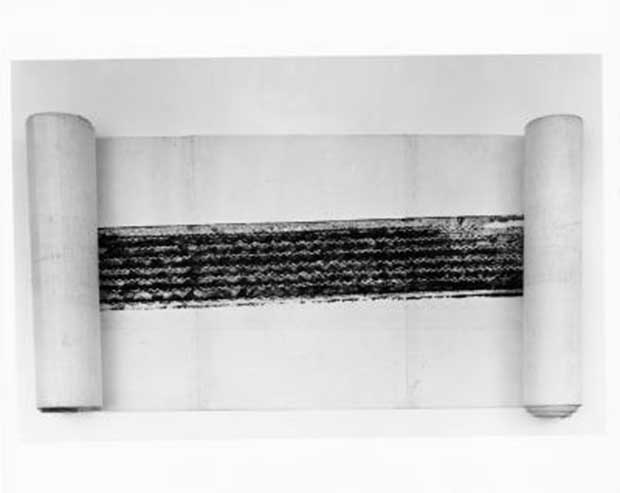

Even if this debt can’t be firmly established, the pair certainly collaborated on another notable, fine art work. In Automobile Tire Print (1953), Rauschenberg got Cage to drive a car, its tyre covered in black house paint, over sheets of paper Rauschenberg had glued together.

Rauschenberg said that Cage was the only driver in Manhattan willing to collaborate on such an unusual scheme. Perhaps this is a suitably flip comment to accompany so brisk a work. When asked if the work is a little like a musical stave, the artist demurred, preferring to compare it to a Tibetan prayer scroll. Yet, Cage drove over Rauschenberg’s scroll in the very same Model A Ford that he had carried him to Black Mountain College in a few years earlier; and doesn’t this single track bring to mind a little something of Cage’s featureless score for 4’33” – the silent work that’s never quite rid of the world’s noise?

For more on Rauschenberg’s work, consider our Phaidon Focus monograph; meanwhile for more on how his and Cage's relationship helped influence the development of painting in the 20th Century, buy a copy of our overview, Painting Beyond Pollock.