My Body of Art - Bill Arning on Sucking Toe

We ask prominent artists, curators, collectors and academics to talk about how an artist's work affected their work. Here Bill Arning, director of the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, discusses Peter Hujar's work and more

Anyone who has spent a little time in one of the world’s great art institutions will realise that the paradigms of human beauty have changed over the centuries. Once the ideal was captured in the fecund, prehistoric figures such as the Venus of Willendorf; later it was expressed via the drawing-room beauty of John Singer Sargent’s Portrait of Madame X. Yet how do these depictions change over a shorter span of time?

In a really illuminating interview with Artspace, the veteran US curator Bill Arning describes how recent political, cultural and social developments have changed the way the body is portrayed in art.

Arning, who served as director of White Columns, New York’s oldest non-profit exhibition space, from 1985 until 1996, is currently the Executive Director at Contemporary Arts Museum Houston. He has seen fashions come and go, and he detects a fresh enthusiasm for the body in figurative paintings.

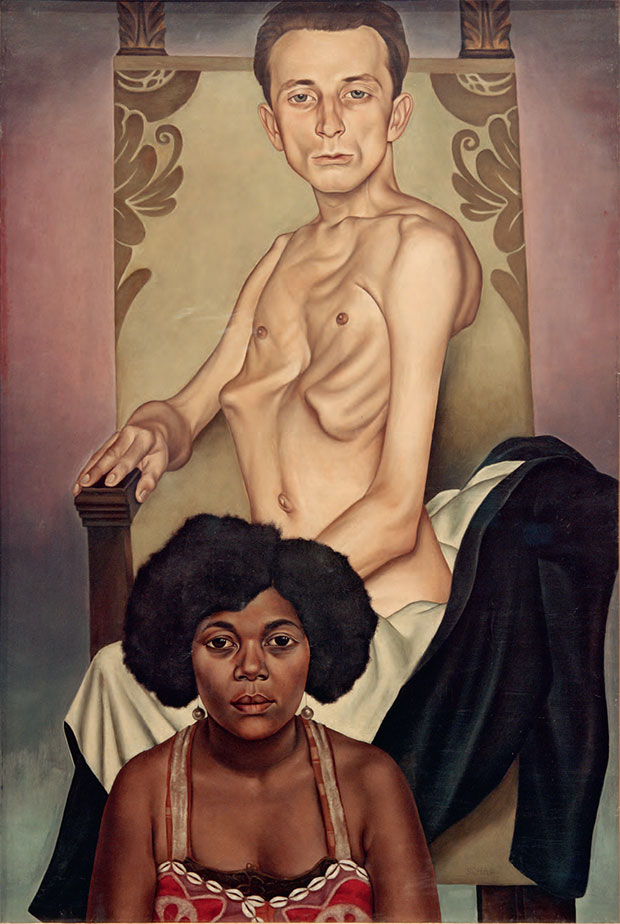

“I saw the “New Objectivity” exhibition of realist painting from the Weimar Republic this summer at the Museo Correr in Venice,” he reveals, in an interview framed around the publication of our brilliant new book, Body of Art. “Those Christian Schad paintings could totally rock through a Lower East Side gallery today.”

However, pre-War Germany is not 21st century Manhattan, and if Schad were painting today, his images would be tempered by contemporary influences. “Now feminism and new thinking about race and sexuality has fundamentally changed portraiture,” Arning says.

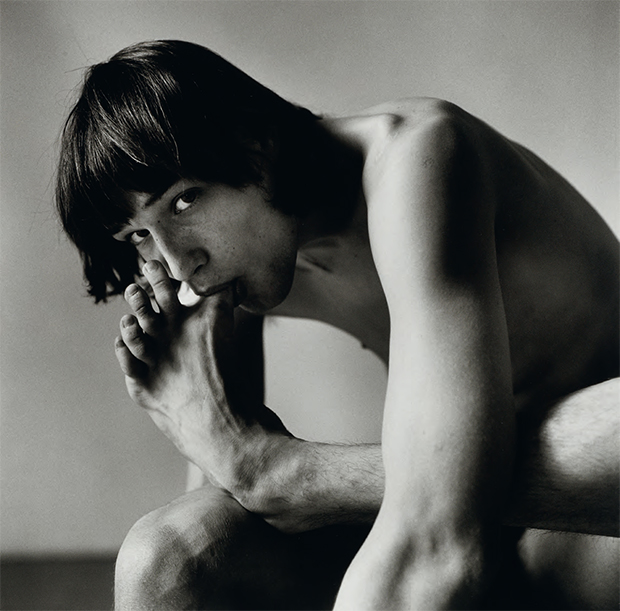

To illustrate his point Arning describes the later life of one of US photographer Peter Hujar’s 1970s subjects, who was a New York ballet dancer. Hujar was known for his photographs of NYC’s gay community, and this particular triptych shows the dancer masturbating to the point of ejaculation. It was a scandalous series of images when first exhibited, and remains controversial today. However Arning says he spent a little time researching this dancer’s later life and discovered that the man married his husband a few years ago, and posted a video of the entire ceremony online.

“I thought, if exhibitionism in 1972 means masturbating for Peter Hujar, and if exhibitionism today means putting your gay wedding up on Vimeo, then that is clearly a watershed change,” Arning says.

Other, more gradual cultural developments have also altered the way we look at bodies. Take our 21st century’s dietary and exercise regimes, which, combined with certain medical advances, enable many of us to achieve a level of personal, physical perfection unattainable in the ancient world.

Arning believes that, when people couldn’t readily improve their own bodies, they instead sought bodily perfection in art. Conversely, with the ubiquity of physical flawlessness, comes a newfound, artistic fascination with corporeal failure and deformity.

“Today we think of bodies as things that need to be fixed,” he explains. “We all have to go to the gym or do yoga or change our diet in order to have a body that is even barely acceptable. It’s the idea that the body is inherently flawed — that science-fiction trope where the computer decides that the world is perfect except for those messy humans, who must be eradicated. In fact, I was going through page after page of Body of Art, thinking, “Those messy humans, yes, they must be gotten rid of. They keep messing everything up.” And I like that. So, our bodies tend to be the flaws in the system, and the book finds ways to celebrate the fleshy and smelly joys of our flaws.

"The thing I liked the most about Body of Art is that, as a contemporary-art guide, I get very nervous when students don’t understand that there’s a continuum running through all of human creation, and that you have to look cross-culturally as well as across time in order to understand it. I like that the book shows that with an active visual imagination, and makes these connections clear."

To gain greater understanding of these movements, see works by Hujar, Schad, as well as the the Venus of Willendor, Madame X, and plenty more besides, buy a copy of Body of Art here.