How Caravaggio, Freud and Dalí saw Narcissus

Discover how this ancient self-obsessed beauty found a place within baroque, surrealist and modern British art

When vanity gets too extreme it edges into narcissism – a modern term for psychological self-admiration that has its roots in classical Greek mythology.

As our new book Flying Too Close to the Sun: Myths in Art from Classical to Contemporary explains, Narcissus was the beautiful son of the water-nymph Liriope. One day, while out hunting, he caught sight of his reflection in a pool, was overcome by its beauty, and attempted to embrace himself. “Yet, every time, the pool would ripple and distort the face of his beloved.”

“It seemed as if the mysterious youth beneath the surface longed just as strongly for Narcissus,” the text goes on, “returning his smiles and tears and trying to reciprocate his embraces” continually, until he died. This is how three great artists have pictured the doomed, vain youth.

Narcissus (1594-6) by Caravaggio Though this Milanese Master painted many fantastical scenes, from the Bible and other sources, it was the realistic, psychologically plausible way he presented his subjects that truly set him apart. “Caravaggio was known for the stark realism with which he depicted people, painting from life and often illuminating unexpected areas of the body (here, the knee) where the light fell,” explains our new book. “Narcissus’s forearms form a circular framework with his reflection, underscoring the vicious cycle of his self-love. He dips his left hand into the water and seems about to embrace his image, his longing palpable.”

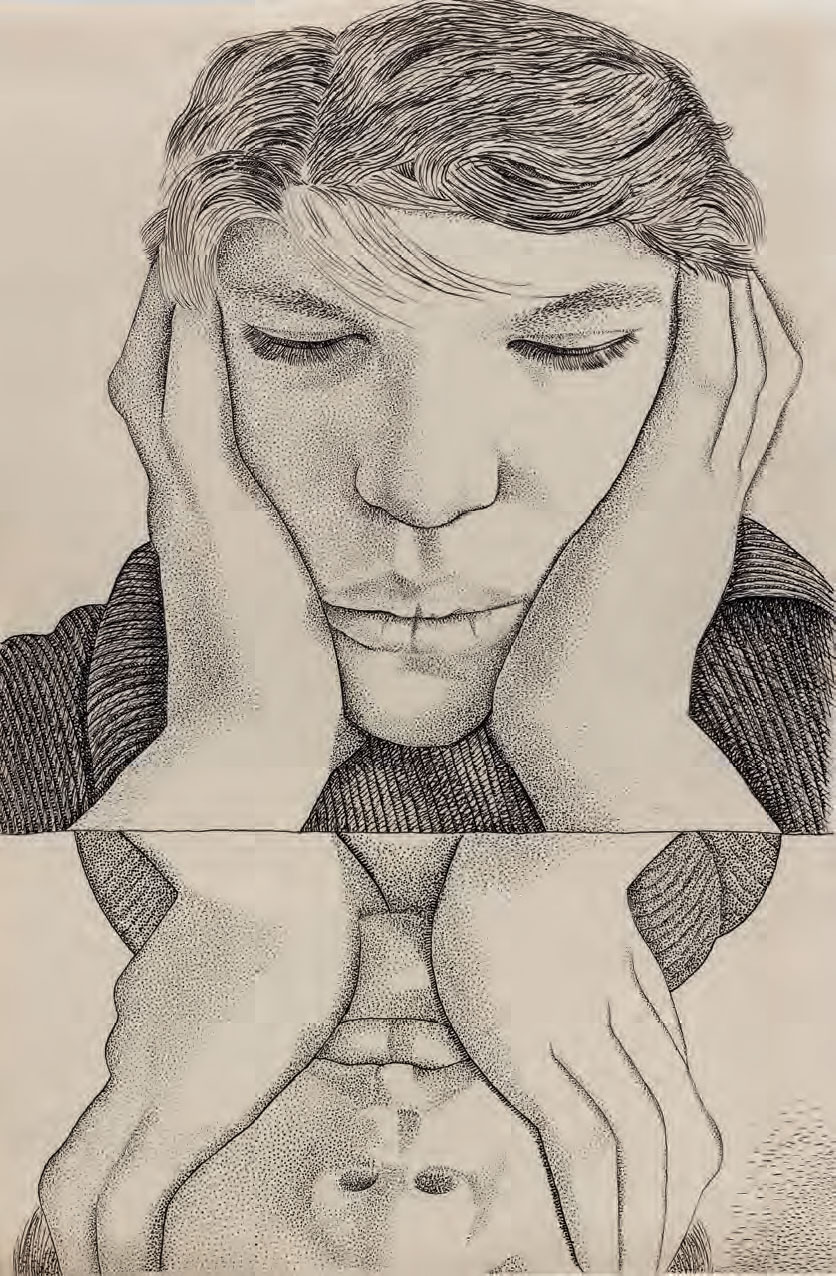

Narcissus (1948) Lucien Freud Freud overcomes the technical problem of reproducing both a man’s face and its mirror image, while emphasizing its gaze, in this 20th century pen and ink work.

“While the man’s nose, mouth and chin are visible, Freud has cropped the inverse image above the eyes,” explains our book, “bringing the focus of the drawing back to the self-absorbed figure.”

Unfortunately, the British artist’s brilliance didn’t satisfy its commissioners – the publishers of Men and Gods, a retelling of ancient myths – who rejected Freud’s suite of illustrations completely.

Metamorphosis of Narcissus (1937) by Salvador Dalí Can you spot Narcissus in this picture? He actually appears not once, but three times, as Dalí tells Narcissus’s whole story in one work. “A stylised figure representing the Greek youth Narcissus kneels at the edge of a pool of water with his head bowed [far left]” explains our new book. “The nearby sculptural hand at the water’s edge mirrors his crouching form; its fingers hold a cracked egg from which grows a narcissus flower [the flower that sprang up in his place, following his death].”

“Beneath the imposing cliffs in the background is a group of people – rejected lovers who now mourn the loss of the handsome youth,” the book goes on. “The youth as he was before his transformation is seen in the background, posing alone on a plinth. The artist’s attempt to paint the entire myth in a single canvas gave him the opportunity to develop further his characteristic use of double images, clever visual illusions that had grown out of his interest in hallucination and delusion.”

For more modern art based on ancient myths, and lots more besides, order a copy of Flying Too Close to the Sun here.