13 things we learned from Jean-Michel Othoniel’s new interview

Read how childhood museum visits and spells in New York and Paris formed this entrepreneurially-spirited artist

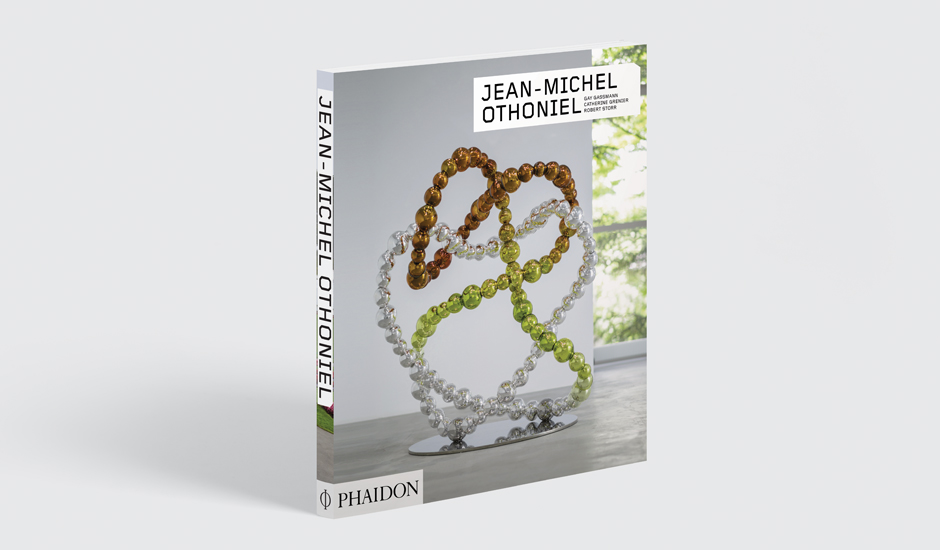

There’s no artist quite like Jean-Michel Othoniel. The French sculptor’s ornate, colourful artworks are both disturbing and delicate. Using distinctive modular elements, such as glass bricks and beads, his pieces often hint at loss and despair, while also grappling with themes of fragility, transformation, and ephemerality. The works can range in size from intimate, gallery pieces, through to monumental public commissions, many of which have been installed in prominent settings around the world.

How did the boy from provincial France develop into an internationally recognised art-world figure? In our new Contemporary Artist Series book devoted to Othoniel, he tells all, in a frank interview with the writer Gay Gassmann. Here are a few highlights from their talk.

Othoniel went to a state-run school in Saint-Étienne, an old coal-mining town, yet he still had a cultured upbringing “Saint-Étienne was a Communist town and all the state school pupils visited the museum every Wednesday afternoon,” he says. “I remember when I was six or seven, I loved going to the museum and listening to the stories behind the paintings.“

The works in that local museum were pretty challenging “The Saint-Étienne museum is second only to Centre Pompidou for modern art in France. The curator had close ties with Ileana Sonnabend, the great art dealer. He collected a lot of American contemporary art. As a child, this museum was my window onto hope, a space where you were allowed to be different.”

Othoniel’s education continued apace, when he went to Paris, to study art, in 1981 “It changed my life profoundly. It was at the beginning of the big projects of the newly elected President François Mitterrand. A new government carried us with it, expanded our understanding, and we voted for laws that made society more equal. In 1981 the death penalty was abolished, in 1982 homosexuality was decriminalised and life changed for millions of people – including me. This was right at the beginning of my youth, of my studies, and I felt free. Everything was exploding. I discovered Louise Bourgeois at the Paris Biennale, the crazy parties at le Palace and its mix of artists. For someone like me from a small provincial town, this was huge.”

That sensation of freedom continued, when he visited New York, later that same year “Two bombshells in the same year: getting to Paris and discovering New York! I remember seeing some Keith Haring drawings in the subway and also being bowled over by the ambitious museums and their collections. All that was nourishment to me. I discovered that there would be no limits to the family of artists who welcomed me in.”

The thrill of these early years were tainted with fear too “These were the years haunted by AIDS. We were all about twenty-two years old and many students died among us, in unbelievable pain, disfigured by this illness. I lost many friends to this disease.”

The fear of AIDS, combined with the strong commercial drives of the age informed Othoniel’s art “There were two visions of the body confronting each other at that time: the body as suffering, diseased, which stood opposed to the body idealised and manipulated by advertising. One began to see naked men and women in magazines, something that you previously could only have seen in some specialist journal. There was the spectre of an ultra powerful body, super beautiful, very erotic, very seductive, a body built as opposed to a body in demise, sick, whose emaciation and carcinomas were terrifying.”

And speaking of commercial drive, Othoniel struck quite a strange deal to finance himself in those early days “There was a young gallerist on my graduation panel. He asked me how much my parents gave me each month to live off (it was the equivalent of around 300 Euros today). He suggested giving me the same amount for five years in return for ownership rights to everything I made in that time. I didn’t know about the art market; it was a notion that had never been part of our studies. I had lots of friends who were trying to become artists and who’d taken jobs to pay the bills. I thought I’d have nothing to lose and everything to gain, especially in terms of freedom. He fulfilled his part of the deal. I was able to do my first solo show at the FIAC the following year. At the time, money didn’t have priority over art, and Paris was still a city where you could manage to get by.”

Othoniel first exhibited glass artworks in 1997 at The Venice Peggy Guggenheim Collection, partly thanks to a clever lawyer These early works in glass were very small, quite sensual, like forbidden fruit or phalluses hanging in the trees of Peggy Guggenheim’s garden. At the time, the Guggenheim didn’t show contemporary artists in Venice. It only showed the collection as stipulated in Peggy’s will. I managed to exhibit thanks to Sandro Durso, a wonderful lawyer, and thanks to Sophie Angremy and Marie Brandolini, who loved my work. The lawyer had perused Peggy Guggenheim’s will, where all the furniture had been outlined – in the bedroom, dining room etc. – and nothing could be moved. But he’d found some trees that weren’t stipulated in the will. The discovery of this loophole amused the director so much that he took my project to the Board in New York, who ended up approving it.”

Othoniel also scored a major public commission Kiosk of the Nightwalkers, a few years later in Paris, which which went on to become quite a tourist attraction “This work has been listed in all the guides to the capital since 2000, which has been fantastic for me. It would have been a nightmare if it hadn’t been well received. Kiosk of the Nightwalkers was just controversial enough at the beginning for people to have an opinion about it. Today, this little glass pavilion is the only remaining trace of the year 2000 in Paris.”

A couple of years later, his solo show, Crystal Palace, which ran from late 2003 until early 2004 at Fondation Cartier, really connected Othoniel to some key art world figures “It was thanks to this exhibition that I met the American architect Peter Marino. It was also at that time that you and I began to work together. These were new visions that appeared in my life. Working with an architect like Peter and responding to the demands of commissions in response to his architectural spaces gently led my work towards the monumental. Then we did several projects together, each crazier than the last. And at the same time, I began to work with the gallerist Emmanuel Perrotin in Paris.”

Around the same time, Othoniel stopped living so hand-to-mouth “I was forty-years-old and it was at that time that I really began to make a living from my work. Until then, I was just getting by like a student. It was also around this time that the art world began to converse with the world of fashion and the world of finance. We stopped talking about the art world and began to talk about the art market. Art had become fashionable.”

Despite this success he’s still proud to remain a bit of an art-world loner “From the start, I’ve always been quite a singular artist, and I’ve also had the strength to be different. The only advice I can give to a young artist is to be unique. That frequently involves great solitude, but it doesn’t necessarily mean being misunderstood.”

If he was asked to advise younger artists, he would only offer a few simple words of guidance “The only advice I can give to a young artist is to be unique. That frequently involves great solitude, but it doesn’t necessarily mean being misunderstood. I’ve always viewed this solitude as an opportunity, as a particular island where I can to go to find myself. I love artists who are different from others.”

For more delicate, breathtaking art, and plenty more personal insight, order a copy of our Jean-Michel Othoniel book here.